Neural Babel: What Do Neural Networks Talk About?

Translating internal representations of neural networks into natural language.

Code for this project can be found at: https://github.com/sike25/neural_syntax

1. Introduction

Imagine overhearing a conversation in a language you don’t speak. The speakers understand each other perfectly, but you have no idea what they’re saying. In this project, the speakers were neural networks, and the language emerged spontaneously when they were trained to collaboratively solve a task. We tried to build a translator for this “neuralese” and this is what we found.

Me trying to understand neuralese

2. Teaching Machines to Point at Things

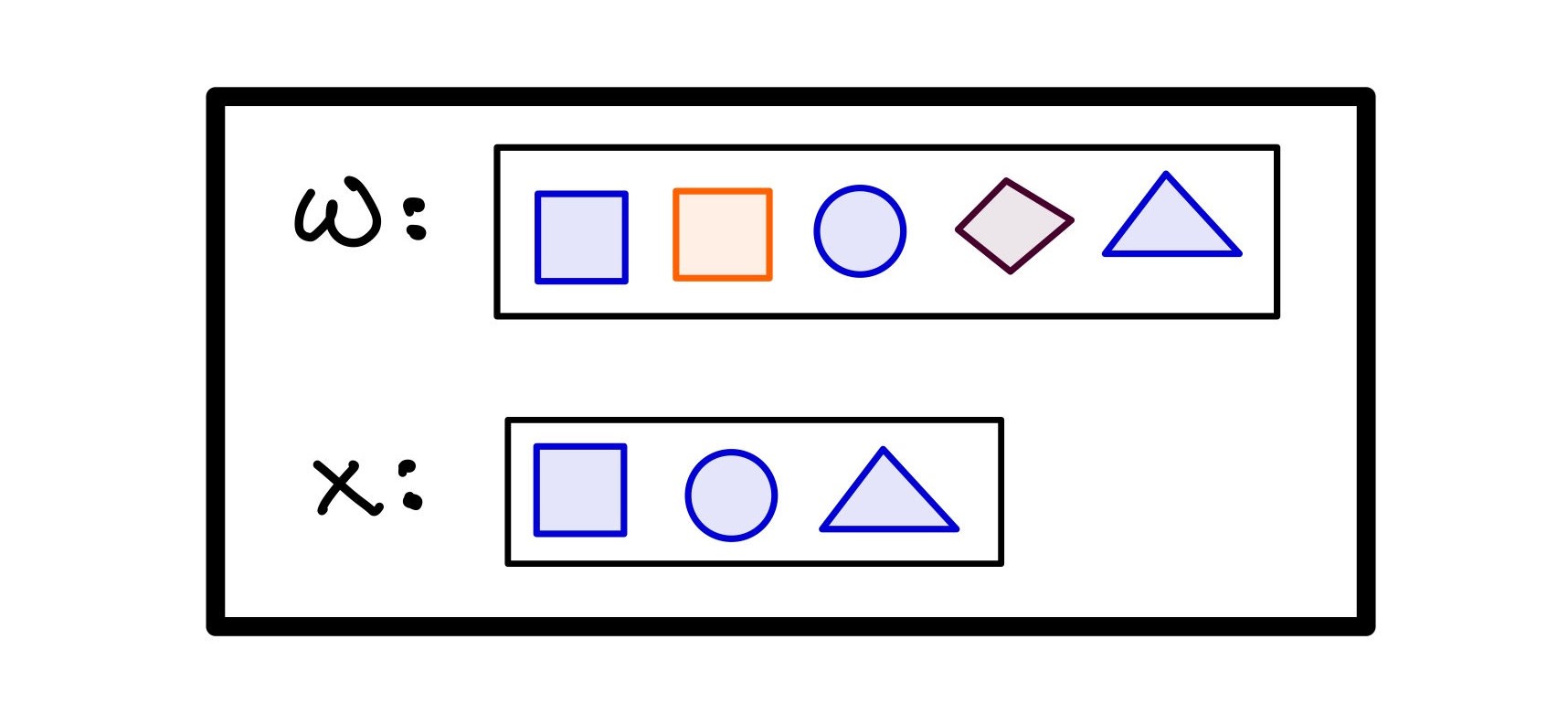

Take a world of objects W and a subset of this world X.

Fig. 1. A world W of objects has a subset X decided by some rule.

Before scrolling, how would YOU describe this selection?

Look at the rule

RULE: ‘blue’

A neural network called the speaker is given

Andreas and Klein (2017)

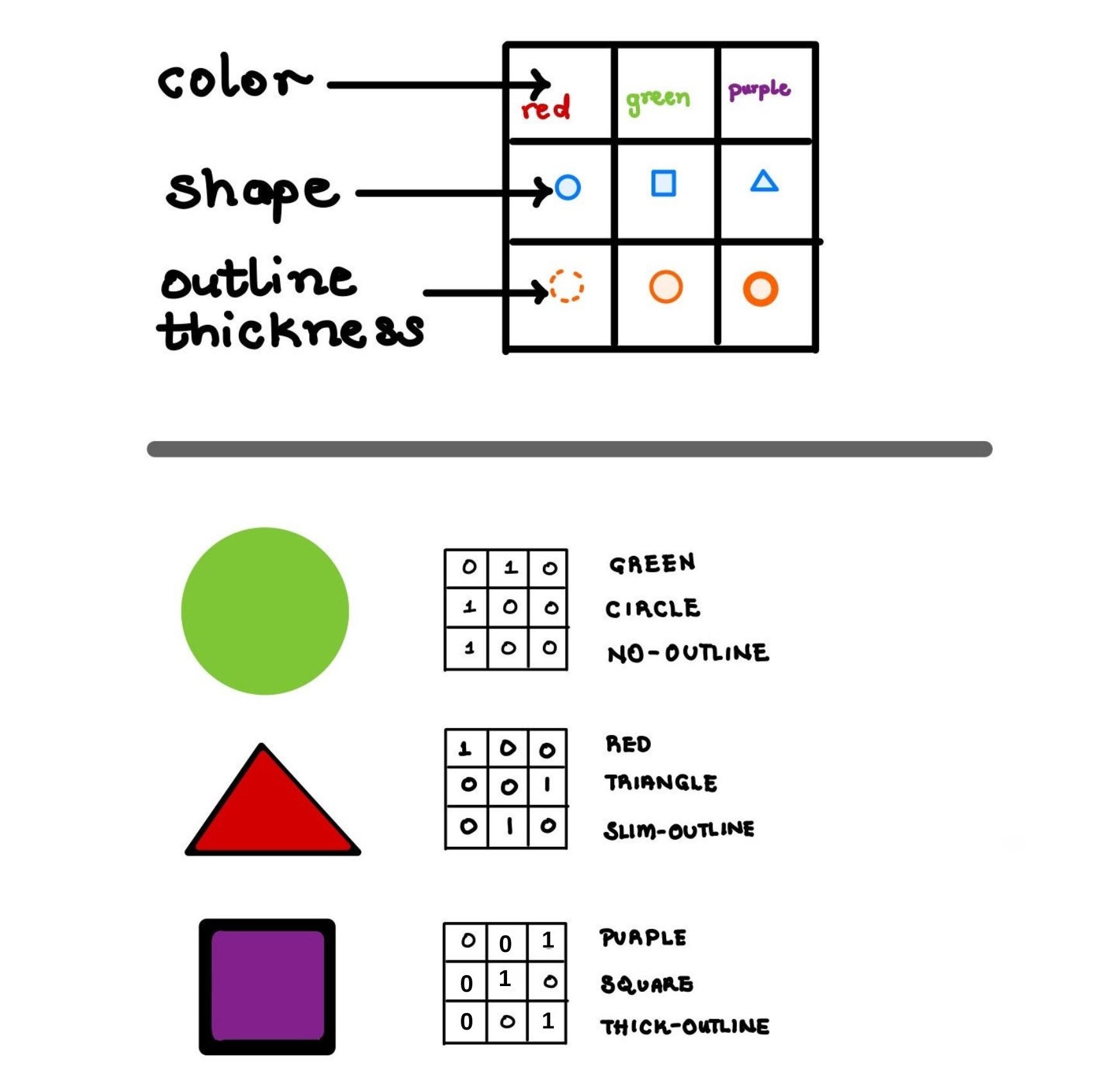

For training data, Andreas and Klein use labels from the GENX dataset

Fig. 2. An object

Our dataset had 80,730 unique worlds of 5 objects each. Subsets were created using 72 unique rules: single feature rule red, single feature negation not red, two features of different types joined by and/or red and circle, triangle or thick-outline. Skipping over world-rule combinations that resulted in empty subsets, we gathered a dataset of 1,705,833 (world

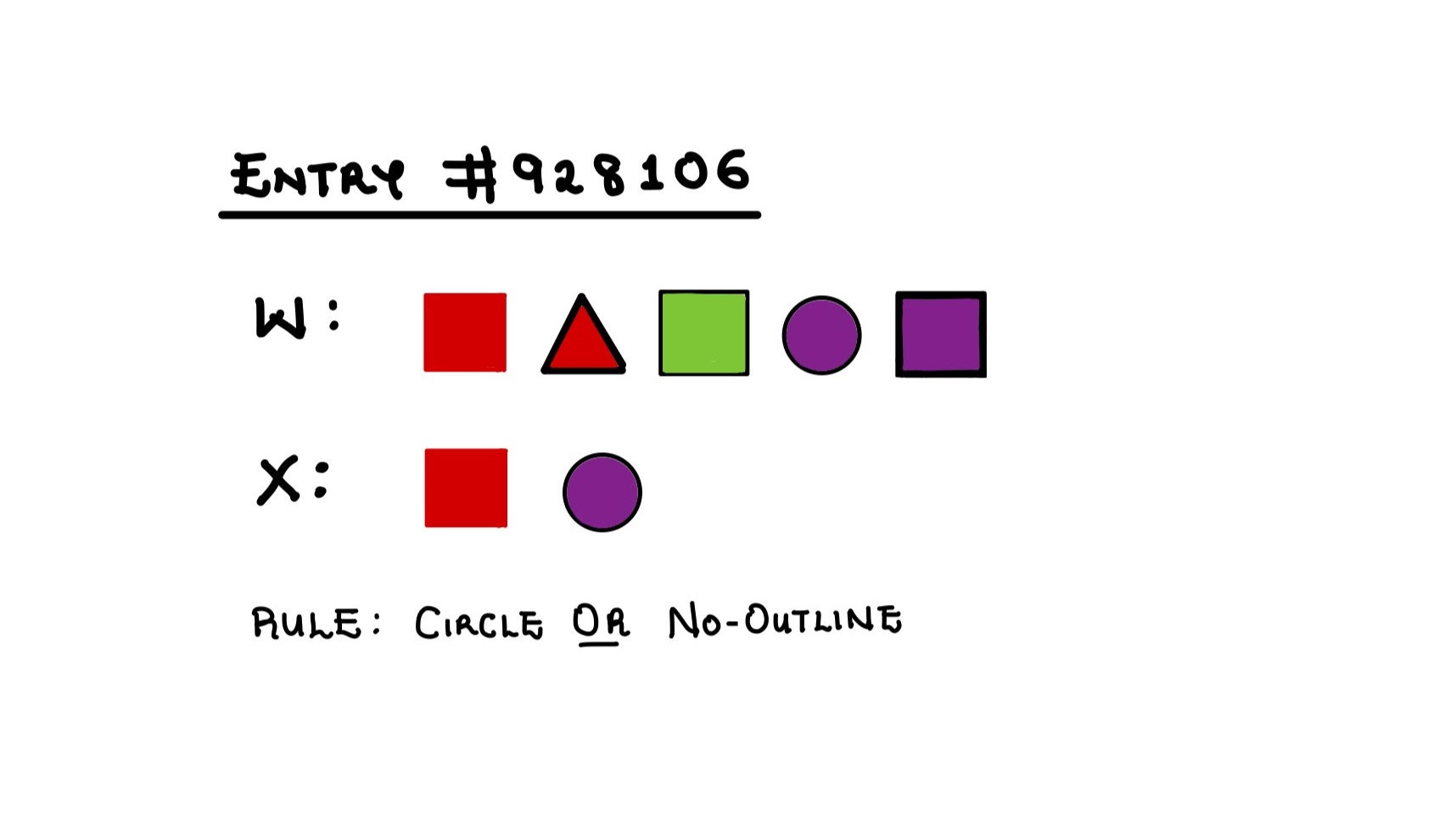

Fig. 3. An entry from our generated dataset.

Training separate networks to evolve languages in order to play a communication game has also been done in Gupta et al. (2021)

3. Conference

3.1. Training the Speaker-Listener

The speaker-listener system achieved 99.56% test accuracy on an unseen test set, with accuracy climbing from 60% to 95% by epoch 1, implying that the task was easily learned.

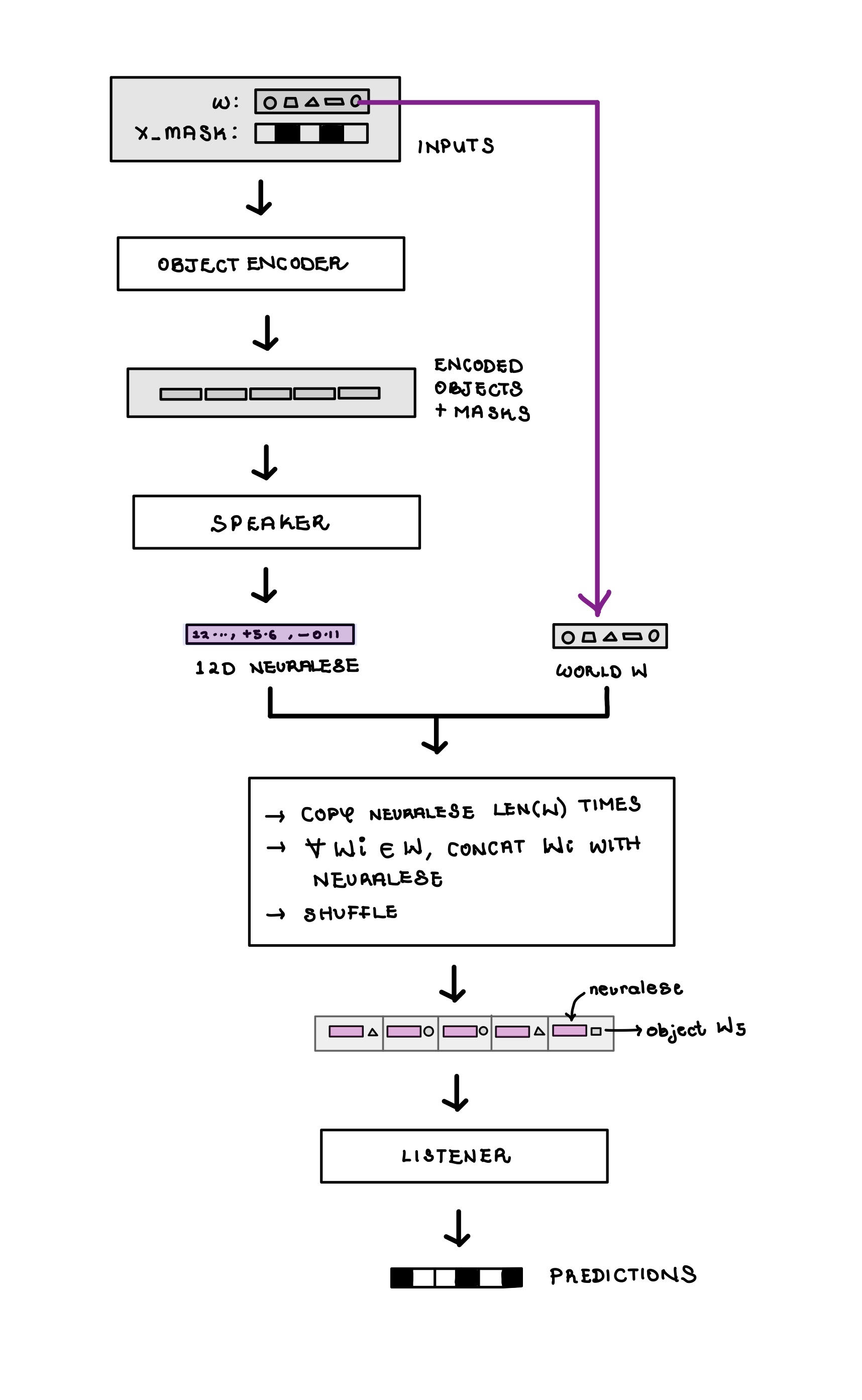

Fig. 4. The Speaker-Listener Architecture.

To prevent the speaker from encoding positional shortcuts (“select positions [0,2,3]”) and force it to learn semantic rules (“select purple circles”), the world objects are shuffled before being fed to the listener.

3.2. Cross-Rule Validation - The Baseline Signal Problem

After training, we needed to verify that the speaker actually learned to encode rules meaningfully. Did “red objects” produce similar neuralese across different worlds? Did red neuralese differ significantly from triangle neuralese?

Using the trained speaker, we generated 100 neuralese vectors each for 9 different rules (like red, green or triangle, not purple, etc.). Then we measured how similar these vectors were to each other using cosine similarity. We expected that neuralese for the same rule should be similar (high within-rule similarity), while neuralese for different rules should be different (low cross-rule similarity), but the similarities for both categories were high (

We guessed that the neuralese might contain a massive “baseline signal” that concealed the actual messages. So we normalized the neuralese by computing the average vector across all examples, then subtracting it from each vector. This brought the cosine similarity for same-rule neuralese down to

This analysis showed that rule information did exist in the neuralese, just hidden beneath the baseline. We therefore inferred that we should normalize the neuralese before attempting to translate them.

4. Translation

4.1. Training the Translator

Having established that the speaker-listener system could communicate, the central question comes up. Can this emergent neuralese be translated into natural language?

If the neuralese vectors have encoded semantic information about the rules, then an appropriate neural network ought to be able to reverse-engineer these rules from the vector alone.

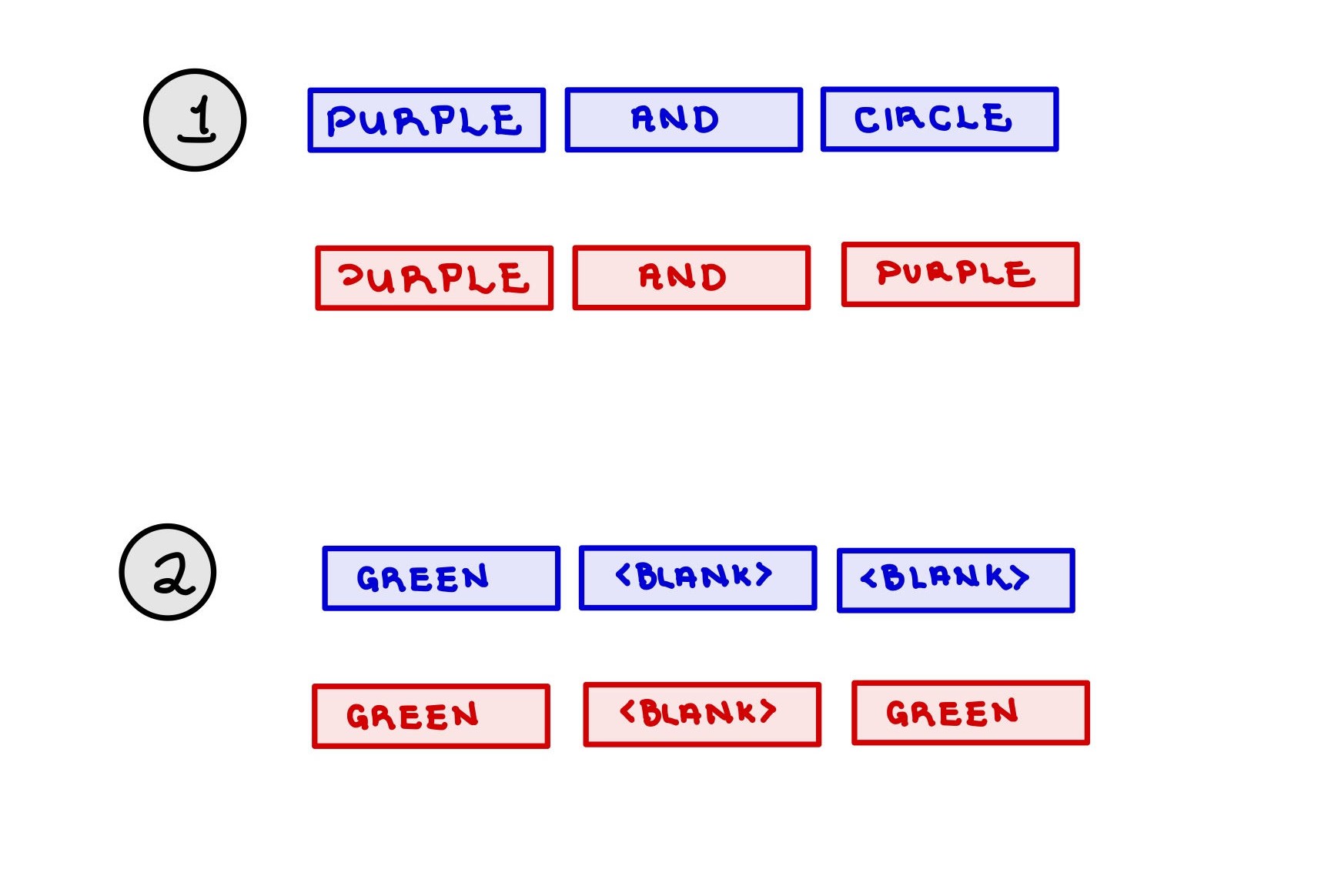

The translator network is a 5-layer multilayer perceptron which takes a normalized 12-dimensional neuralese vector as its input and outputs a 3-token sequence which it classifies over our 13-word vocabulary (9 features + and, not, or + <blank>). The translator was trained on 1,364,666 training examples (40% of the dataset).

Evaluation on an unseen test set yielded modest results. The network correctly predicted individual tokens 63.76% of the time, and got the entire 3-token rule right 38.17% of the time.

4.2. Adjusted Evaluation Metrics

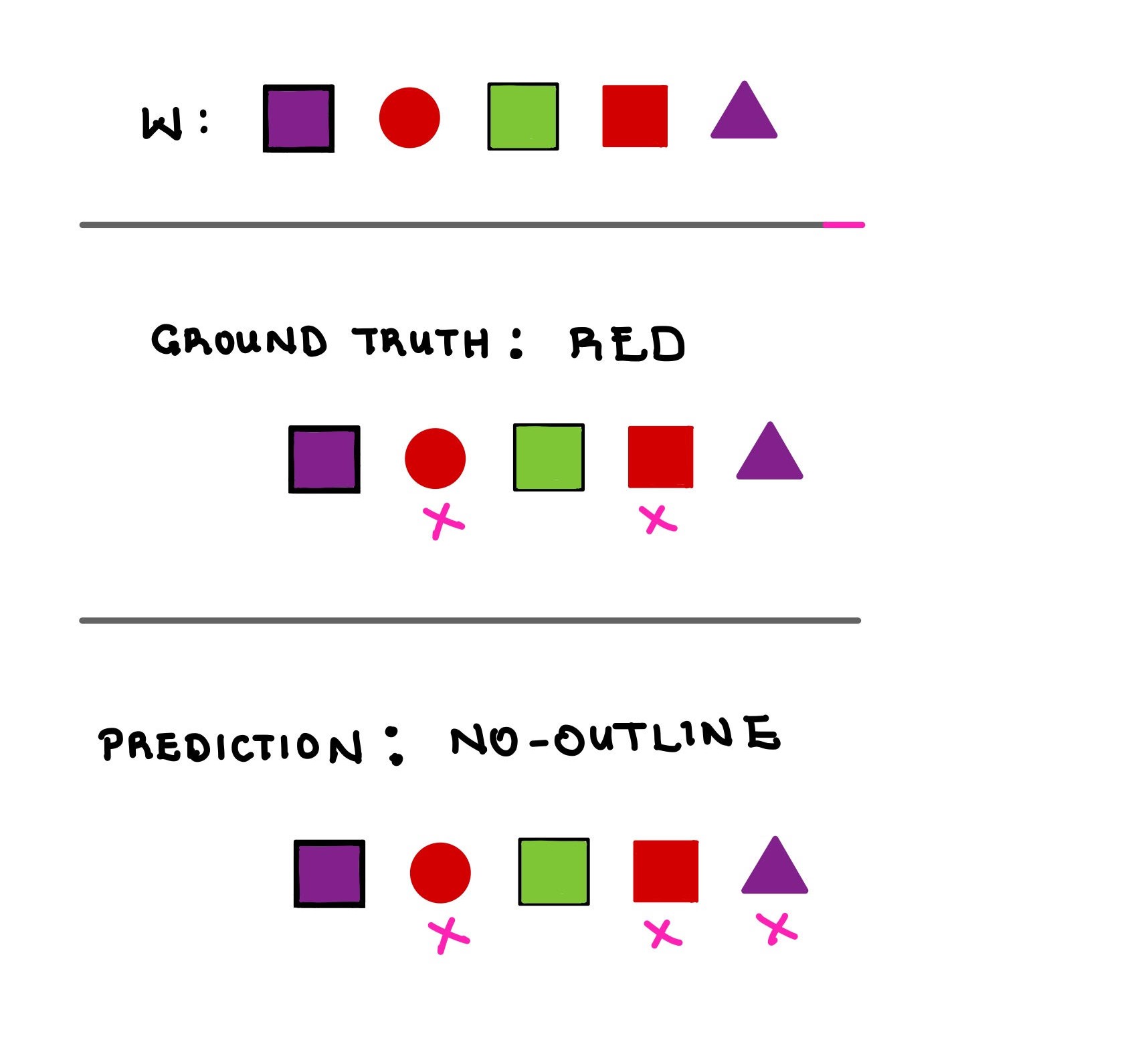

Next, we considered the possibility that raw accuracy metrics could be painting an incomplete picture. Look at this example:

Fig. 5. Different rules can describe the same target subset.

Notice how different rules can produce the same target subset? We then decided to compute a metric where a predicted rule is accurate if it produces the same subset of the world as the ground truth rule even if it is different from the ground truth rule. We called this the adjusted accuracy and calculated it at 43.24%.

Consider another example:

Fig. 6. Predicted rules can perfectly describe the target subset but include other elements. We can consider this phenomenon a sign of partial learning.

Here, the predicted rule correctly describes all the objects in the target subset even though it incorrectly includes the purple triangle. Another adjusted metric tracked whether the rule correctly describes all the selected objects. We called this the description accuracy and calculated it at 51.44%.

We also found that only 61% of predicted rules were even semantically valid. Here are some real examples of malformed rules from our test set:

Fig. 7. The translator can produce incoherent or malformed rules.

This meant that some portion of the incorrectly predicted rules were not rules at all. So we wondered, if we filtered only for semantically valid predictions, what would the evaluation metrics look like? Conditioning on semantic validity raised the adjusted accuracy from 43.24% to 70.81% and the description accuracy from 51.44% to 84.23%.

| All Predictions | Semantically Valid Only | |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Sequence Accuracy | 38.17% | - |

| Adjusted Sequence Accuracy | 43.24% | 70.81% |

| Description Sequence Accuracy | 51.44% | 84.23% |

5. Conclusions

5.1. What the Cross-Rule Validation Tells Us

Remember our baseline signal problem? After normalization, same-rule neuralese vectors had cosine similarities around 0.246— moderate, but nowhere near the ~1.0 we’d expect if neuralese vectors were perfect rule encodings. The concept of rules exists in neuralese, but neuralese is not equal to the rules themselves.

If neuralese were theoretically equivalent to our selective rules—if red always mapped to some canonical red vector—we’d see cosine similarities approaching 1.0 within rule categories. So we know these vectors are contaminated with other (possibly useful) data. Perhaps information about the specific world being described. Perhaps metadata about the selection itself—how many objects are selected, their distribution across feature types, spatial patterns in the original (pre-shuffled) arrangement.

So the speaker might learn some rule concepts while also exploiting easier statistical patterns.

The concept of rules exists in neuralese, but neuralese is not equal to the rules themselves.

5.2. What the Adjusted Metrics Tell Us

The translator should not have struggled as much as it did to produce well-formed 3-token sequences from such a limited and consistent grammar. However, the strong performance on semantically valid rules suggests that the translation task itself is feasible. The bottleneck appears to be the token-by-token classification approach: the MLP architecture struggled to construct coherent rules when predicting each token independently, even though it could successfully translate neuralese when it did produce valid sequences.