Failures in Perspective-Taking of Multimodal AI Systems

An investigation into the spatial reasoning abilities of multimodal LLMs.

Introduction

Recent research in AI has exposed a critical limitation: the inability of current models to effectively perform spatial reasoning tasks. Despite their impressive visual perception capabilities, these models struggle to understand spatial relationships and make inferences about them. While previous research has explored aspects of spatial cognition in AI, it often lacks the specificity characteristic of human spatial cognition studies. In cognitive psychology, tasks are carefully designed to isolate distinct processes, enabling precise measurement and minimizing bias or reliance on alternative strategies. To bridge the gap between cognitive science and artificial intelligence, we focus on a fundamental aspect of human spatial reasoning: visual perspective-taking.

Visual perspective-taking is the ability to mentally simulate a viewpoint other than one’s own. It allows us to understand the relationship between objects and how we might have to manipulate a scene to align with our perspective, which is essential for tasks like navigation and social interaction.

By leveraging established methodologies, we can rigorously evaluate AI’s spatial cognition, starting with perspective-taking. The extensive human literature on spatial reasoning offers a valuable benchmark, enabling comparisons between model performance and the human developmental trajectory. This comparison helps identify critical gaps and opportunities for enhancing AI models.

Our aim was to create a targeted perspective-taking benchmark for multimodal AI systems, probing various levels and components of the cognitive process.

Definitions and Terminology

-

Level 1 Perspective-taking refers to knowing that a person may be able to see something another person does not

-

Level 2 Perspective-taking refers to the ability to represent how a scene would look from a different perspective

-

Mental Rotation where one imagines an object or scene rotating in space to align with a perspective

-

Spatial vs Visual Judgments responding to queries about the spatial orientations of objects or their non-spatial visual characteristics

Click here to learn more about perspective-taking

In the human developmental literature, perspective-taking has been stratified into two levels, defined above. Based on developmental literature, level 1 perspective-taking appears fully developed by the age of two

A more specific cognitive process, mental rotation, where one imagines an object or scene rotating in space to align with a perspective, plays an important role in perspective-taking. Surtees et al.

Creating a New Benchmark

Limitations of Current Benchmarks

There are two main limitations current AI spatial cognition assessment:

Reasoning with language alone can inflate performance on spatial benchmarks

Text-only GPT-4 achieves a score of 31.4, while multimodal GPT-4v achieves a score of 42.6 on the spatial understanding category of Meta’s openEQA episodic memory task

Benchmark scores can be hard to interpret since models often perform poorly

BLINK

To target some of these issues, we apply established tasks in cognitive psychology that measure spatial cognition in a precise manner. By applying these tasks to AI systems, we gain not only improved measurement precision but also the ability to compare AI performance with human development, providing clear insights into model limitations and areas for improvement.

Perspective Taking Benchmark

Leveraging the distinction between Level 1 and Level 2 perspective-taking

Methods

Our study utilized GPT-4o (“gpt-4o-2024-05-13” via OpenAI’s API) to conduct a series of perspective-taking experiments designed to capture the system’s spatial reasoning abilities. We kept top_p = 0.5 to restrict the model from choosing from the top 50% of words that could come next in its response.

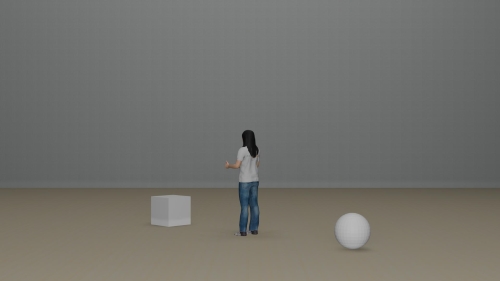

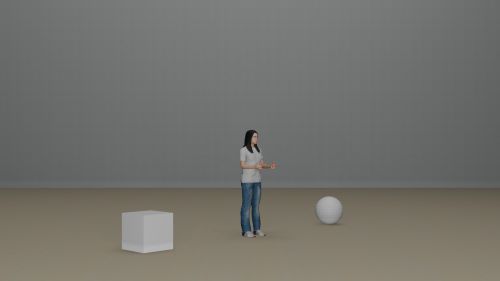

Our experimental design was inspired by previous studies that evaluated viewpoint dependence using targets like toy photographers [2] and avatars with blocks [12]. In our study, we used an avatar as a target and different stimuli, either cubes with numbers and letters or cubes and spheres, to investigate the influence of visual and spatial judgments on model performance. Each task consisted of 16 trial types, featuring images at 8 different angles (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, 315°) with 2 response options for each task (e.g., cube in front or behind, 6/9 or M/W on the cube, and cube left or right).

Ten iterations of each image were passed through the model to calculate the percentage of correct responses.

| Task | Example Stimulus | Prompt |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 |  | For the following images respond with in front or behind to indicate if the cube is in front or behind from the perspective of the person. |

| Level 2: Spatial Judgment |  | For the following images respond with left or right to indicate if the cube is to the left or to the right from the perspective of the person. |

| Level 2: Visual Judgment |  | For the following images respond with 6 or 9 to indicate if the number on the cube is a 6 or a 9 from the perspective of the person. |

| Level 2: Visual Judgment |  | For the following images respond with M or W to indicate if the letter on the cube is an M or a W from the perspective of the person. |

Chain of Thought Prompting

To further examine how language might be used to solve spatial tasks, we included chain-of-thought prompting to the Level 2 spatial task with the prompt:

“Analyze this image step by step to determine if the cube is to the person’s left or right, from the person’s perspective. First, identify the direction the person is looking relative to the camera. Second, determine if the cube is to the left or right, relative to the camera. Third, if the person is facing the camera, then from their perspective, the cube is to the inverse of the camera’s left or right. If the person is facing away from the camera, then the cube is on the same side as seen from the camera. Respond with whether the cube is to the person’s left or right.”

Results

Level 1

GPT-4o performed with near-perfect accuracy on 6 out of the 8 image angles as seen below. Its poor performance on 0° images is likely due to an accidental viewpoint where the avatar blocked one of the shapes. However, poor performance on 315° image types is less interpretable, especially in contrast to GPT-4o’s impressive performance on 45° images, which have the same angular perspective.

Level 2 Spatial and Visual Judgments

As previously mentioned, human response times increase on perspective-taking tasks as the angular difference between the target and observer increases

Chain of Thought

GPT-4o performance significantly improved with chain-of-thought prompting on 180° stimuli. However, this linguistic strategy did not improve the model’s ability to handle intermediate rotations between 90° and 180°. This suggests that while language can convey some level of spatial information, it lacks the precision required for human-level spatial cognition. This demonstration of surface-level perspective-taking abilities can partially explain how multimodal models achieve high performance on certain spatial benchmarks.

Conclusion

With this project, we highlight the value of applying cognitive science techniques to explore AI capabilities in spatial cognition.

-

We investigated GPT-4o’s perspective-taking abilities, finding it fails when there is a large difference between image-based and avatar-based perspectives

-

We developed a targeted set of three tasks to assess multimodal model performance on Level 1 and Level 2 perspective-taking, with spatial and visual judgments

-

GPT-4o can do Level 1, aligning with the spatial reasoning abilities of a human infant/toddler

-

GPT-4o fails on Level 2 tasks when mental rotation is required—the avatar’s perspective is not aligned with image perspective

-

-

We investigated if chain-of-thought prompting could elicit more spatial reasoning through language

- This enabled GPT-4o to succeed on 180° tasks, but it continued to fail at intermediate angles, underscoring its limitations in performing true mental rotation

While GPT-4o’s performance decreases on tasks that humans typically solve using mental rotation, this does not necessarily indicate that GPT-4o struggles with or cannot perform mental rotation. Instead, it suggests that GPT-4o likely employs a fundamentally different strategy to approach these tasks. Rather than engaging in mental rotation, GPT-4o appears to rely primarily on image-based information processing. We found more support for this when testing an open prompt for Level 2 visual images that did not specify which letters or numbers to respond with. GPT-4o often responded with “E” and “0” for images around a 90° angular difference, where from the image view, an M/W would look like an E, and a 9/6 would look like a 0.

It could be that current multimodal models aren’t trained on the appropriate data to achieve the reasoning necessary for Level 2 perspective-taking. However, considering the developmental trajectory of humans, it becomes evident that this issue may not be solely data-related. Level 2 perspective-taking typically develops between the ages of 6 and 10

This project demonstrates the potential of cognitive science methods to establish baselines for AI assessment. Using these well-established techniques, we achieve clear, interpretable measures that are less susceptible to bias. Additionally, these measures can be directly compared to human performance and developmental trajectories, providing a robust framework for understanding AI’s strengths and weaknesses in relation to well-researched human cognitive processes.